Author: Julie Pasqual/Jamuna Jaya Devi Dasi

Yoga is ubiquitous! There seems to be nowhere that this beautiful, ancient practice has not taken root. But sometimes when something is spread out, the true meaning of it gets lost. Sort of like the old children’s game of telephone – where one person whispers something into another person’s ear – and that person speaks into the next person’s ear, and by the time it has gotten all the way around the circle, the original sentence spoken has been completely changed. If those who practice and teach yoga don’t know what it’s original goal was, we may be left with a superficial understanding of something that is much, much deeper than an elegant physical posture.

You may have heard that the goal of yoga is:

- To relieve stress

- To gain flexibility and strength

- To teach one to meditate

- To practice being more mindful

- To help one sleep better

- To maintain an active lifestyle

- To become a calmer, less reactive person

While all of these are all wonderful things, none of them are the actual goal of yoga. What is remarkable about this practice is that it has many side effects – and they are all good (like the ones listed above). But what tends to happen, is that people are mistaking the side effect for the actual goal. In the language of Sanskrit, the word for this grand finale of the yoga practice is called Samadhi.

Why the need to attain Samadhi?

To understand why Samadhi is the goal of yoga, first we need to address the predicament that pretty much every human being has – we think we are something that we are not! We think we are a body and a mind, when those are things we have, not what we are. It’s sort of like thinking you are your car, instead of the person driving the car.

Yoga philosophy 101 is that we are not our bodies, nor our minds, we are eternal souls. In the second chapter of the Bhagavad Gita, Krsna spells this out for us:

- 2.20: For the soul there is neither birth nor death at any time. He has not come into being, does not come into being, and will not come into being. He is unborn, eternal, ever-existing and primeval. He is not slain when the body is slain.

- 2. 23: The soul can never be cut to pieces by any weapon, nor burned by fire, nor moistened by water, nor withered by the wind.

- 2.24: This individual soul is unbreakable and insoluble, and can be neither burned nor dried. He is everlasting, present everywhere, unchangeable, immovable and eternally the same.

But, every time the blissful, knowledge soul takes on a body, it comes with a wonderful machine called the mind, whose job is to think. And, it does it’s job very, very well. As it churns out thought after thought after thought, the soul begins to forget that it’s not this mind (like us forgetting we aren’t our car) and so it is caught in a web of things that effect the mind and the body, but don’t really effect the soul. Sort of like the way we can get so elated or deflated when our favorite sports team wins or loses. We can feel our heart beating faster as the seconds of the game tick off, we scream, we yell, we cry – but none of what we are watching is actually happening to us! So, we are trapped reacting to things that, in reality, are not our problems, but very much feel like they are. And, this is where Samadhi comes in.

So, what is Samadhi?

Samadhi is that state where the soul frees itself from the trap of the mind, and is able to perceive itself.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali lay this out in the second and third line of the text:

- 1.2: Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of the mind.

- 1.3: When that is accomplished, the seer (the soul) abides in it’s own true nature.

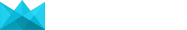

Samadhi, it might be said is the soul recovering from the worst case of amnesia ever! In Ashtanga Yoga – named for it’s ashta (eight) step process, Samadhi sits as that eighth practice that the other components: Yamas, Niyamas, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, and Dhyana lead to. In this system of yoga, though things are in a list, it is not usually said to be necessary to prefect one of the steps to move onto the other. The regulations of the Niyamas don’t have to be prefect before you can do a down dog (thank goodness, because I personally would never be on my mat if that were true!) However, in the case of Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi, the perfection of the first two are what leads to the third.

For Samadhi to be reached, first, one must concentrate (Dharana), and when the focus is held long enough and deeply enough that morphs into meditation (Dhyana), where the strands of the mind are weaved into one unit. And if that state is held long enough, only then is Samadhi reached.

One might ask what the difference is between the deep meditative state that is Dhyana, with the absorption of Samadhi. Here is the detail that separates these two states: In Dhyana, although the mind is being brought to a singular point, the yogi is still aware of outside elements. They would still feel the air at the tip of their nose, or feel the weight of their legs on the ground, for example. They may not be distracted by it, but they do know it’s there. In Samadhi, the only thing the soul can perceive is it’s own eternal, wise, and blissful nature – everything else has fallen away.

Samadhi: a state of intense concentration achieved through meditation. In Hindu yoga this is regarded as the final stage, at which union with the divine is reached (before or at death).

Gradations of Samadhi

Just as one can say that Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi are gradations of each other, Samadhi itself has different levels. One level is called Samprajnata-Samadhi, the other Asamprajnata-Samadhi.

Here is the major difference between the two:

- Samprainata-Samadhi still uses the mind as a prop. It uses the mind to cultivate absorption first in a particular focal point, then in the more subtle or energetic aspects of that particular focal point, then with the blissfulness that is the actual state of the soul, then finally, the mind helps the soul to see. In other words, all those labels, “I am tall, I am short, I am an American, I am a European,” are actually not correct. The mind in this Samadhi has been an aid in getting itself out of the way. (Yoga Sutras 1.17)

- Asamprajnata-Samadhi (this is the ultimate in Samadhi) where the soul is not aware of anything, needs no support at all to see only itself. All thought has been shut down completely. (Yoga Sutras 1.18)

What focal point is powerful enough to achieve Samadhi?

In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali gives a list of possible focal points for the mind. But, he states that only one of them brings the perfection of Samadhi – Isvara Pranidhanai, meaning to surrender to a Higher Power.

This concept of Isvara Pranidhanai is a link between Ashtanga Yoga and Bhakti Yoga. For the Bhakta (practitioner of Bhakti) there is ONLY thinking about the Lord as a means of meditation. The names, forms, and activities of The Divine are what the Bhakta cultivates in their minds and cherishes. And, because Bhakti is what is called a “grace tradition,” The Divine, seeing the Bhaktas dedication, actually enables them to focus on Him. As Krsna says in Bhagavad Gita 10.10, “ To those who are constantly devoted to serving Me with love, I give the understanding by which they can come to Me.” The Yoga Sutras also say this (1.23), “Previously mentioned state of Samadhi is attainable from devotion to The Lord.”

Whatever the focal point of the yogi’s meditation that ripens into Samadhi may be, the fruit is that state where the soul, who has traversed through so many bodies, for so many lifetimes, finally comes home to itself… Samadhi.