I adore the feeling of floating off my mat after Śavāsana, feeling strong and limber, my hips yielding gracefully to every step, and my mind ever-so quiet. This post-yoga experience is no accident, but rather the result of deliberate sequencing and a well-thought-out lesson plan. As yoga teachers, if we lack a clear objective and an anatomically-informed roadmap to get there, it will likely be harder for our students to retain the lessons that lead to greater body awareness. Leading structured āsana classes offers our students opportunities to not only connect deeply with the postures, but also calm and focus their minds. It’s important to pick one thing to teach and teach it well.

It can be intimidating to lead a back-bending sequence because backbends involve so many moving parts that must be addressed throughout the class to ensure students practice these particular āsanas safely. If the body is not properly warmed up, back-bending could lead to discomfort or injury in the lower back or shoulders. As is true for all āsana sequences, but is especially important for back-bending, each pose should serve a purpose.

Let’s take Wheel Pose (Ūrdhva Dhanurāsana), for example. This āsana is an intense backbend that expands the chest, but with support from the core and the hips. To prepare your students for this pose, incorporate postures like Upward Facing Dog Pose (Ūrdhva Mukha Śvānāsana), Plank Pose (Phalakāsana), Locust Pose (Śalabhāsana), and Cow Face Pose (Gomukhāsana), which engage and open the chest and shoulder muscles. With equal importance, address the muscles involved in hip extension, which is when the angle of the hip joint increases. In order for the hips to extend and the spine to bend backwards, the abdominal and iliopsoas muscles must be properly warmed up.

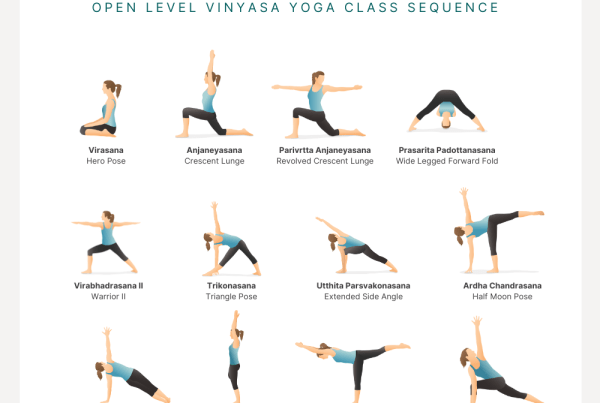

The psoas muscle starts at the Thoracic spine (T-12), hugs the lumbar vertebrae, and attaches to the top of the femur bone (thigh bone). It flexes the hip joint and stabilizes the spine. Because it connects to the lumbar vertebrae and stretches when the hips extend, working the psoas through various āsanas like Low Lunge (Aṅjaneyāsana), Warrior I (Vīrabhadrāsana I), and Extended Side Angle Pose (Utthita Pārśvakoṇāsana) is essential to supporting and preventing injury to the lower back in back-bending postures. Along with various abdominal exercises and core-activating āsanas like Half Boat Pose (Ardha Nāvāsana), incorporating several rounds of various Sun Salutations (Sūrya Namaskar) will help students generate the internal heat needed to open their bodies in a pose like Wheel.

Those are the essential components of a back-bending class. But arranging poses together is not the same as teaching something specific. Within this framework, what insight or information can we offer our students to help them experience Wheel Pose in a new, deeper, more effective way? Let’s circle back to hip extension, which is a mechanism of Wheel Pose. But this posture, among others, also reveals something interesting about hip extension. In Wheel, the hips extend so the spine can bend backwards, but hip extension itself requires the strength of the legs in order to effectively support the backbend. And therein lies the focus of the class – the glutes and hamstrings.

Teach back-bending but do so in terms of how the glutes and hamstrings work in these postures. In Bridge Pose (Setu Bandhāsana), cue your students to engage these muscles to support the elevation of their hips. In Locust Pose (Śalabhāsana) and Bow Pose (Dhanurāsana), hip extension alone does not account for each action; the hamstrings and glutes facilitate the lift we experience in these postures. As well, include āsanas like Garland Pose (Mālāsana), Chair Pose (Utkatāsana), and Warrior 2 (Vīrabhadrāsana II), among others, for building leg strength. When it comes to Wheel Pose, make the connection for your students between these leg muscles, hip extension, and the backbend. Engaging the hamstrings and glutes specifically, along with all the leg muscles, stabilizes the hips so the spine can bend backwards in one fluid arc, without compressing the lumbar spine.

Keep in mind the purpose of āsanas; they are postures, intricate compositions of skeletal alignment and muscular engagement intended to keep our bodies fit for what they contain – our souls. As technical physical shapes, āsanas require time and attention to detail; and as gateways to Spirit, call for sincerity and reverence as well. By sequencing with purpose, we offer our students something to focus on, rather than their fluctuating thoughts, revealing the true gift of āsana: when our minds are steady and calm, soul-nourishing truths begin to emerge